Lemon Juicer Merkel: Where the Real and the Fictional Europe Meet. Exploring Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo

Jasper Delbecke

Abstract

By exploring Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo, this paper seeks to demonstrate how Europe’s resort to its past is more than a desperate answer in the absence of a new narrative for the future of Europe. As I will show, this nostalgic reflex is part of a broader phenomenon that is both a response to and a symptom of a temporal crisis, emphasizing our inability to cope with the past and to imagine alternative futures. With Domo as an instrument, and with the insights of Andreas Huyssen, François Hartog and Svetlana Boym as a theoretical framework, I will explore how theatre practices can help to overcome our inability to deal with the recalcitrant past.

Keywords: Thomas Bellinck, Europe, musealization, monumentalization, performative installation, politics of memory, politics of history

Door Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo te ontvouwen wil deze bijdrage aantonen dat Europa’s vlucht in diens verleden meer is dan een wanhopig poging, bij de afwezigheid van een nieuw verhaal voor Europa. Zoals ik zal onderzoeken, maakt deze nostalgische reflex deel uit van een groter fenomeen dat zowel het antwoord is op alsook het symptoom is van een temporele crisis waar uit onze onmogelijkheid blijkt om met het verleden om te gaan en deze in te zetten voor de toekomst. Met Domo als instrument en de inzichten van Andreas Huyssen, François Hartog en Svetlana Boym onderzoek ik hoe theater ons toch kan helpen om met dat weerbarstige verleden om te gaan en die temporele crisis te overkomen.

Keywords: Thomas Bellinck, Europa, musealisering, monumentalisering, performatieve installatie, politiek van de herinnering, politiek van geschiedschrijving

Full text

Lemon Juicer Merkel: Where the Real and the Fictional Europe Meet.

Exploring Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo

Introduction

In his renowned book The World of Yesterday, Austrian writer Stefan Zweig describes in detail how the nineteenth century – ‘the world of security’ as his first chapter labels it – flows into the twentieth century. Meticulously he writes how his world – a privileged bourgeois world – is challenged by the arrival in Europe of ethnic and social conflicts and the growth of conservatism and nationalism. Zweig’s autobiography, the product of a cosmopolitan intellectual, is a genealogy of what led to the rise of National Socialism, which contributed to the Second World War. Zweig notes that ‘it remains an irrefragable law of history that contemporaries are denied a recognition of the early beginnings of the great movements which determine their times’.1 Outraged and disillusioned, Zweig looks back and wonders how it was possible for people to be blind and ignorant of the danger and contagiousness of hate speech, mass movements and extreme nationalism. Although the negative signs were already present by the end of the nineteenth century, they were seen as marginal and harmless. By the turn of the century, nobody would dare to predict the horror and atrocities the 20th century would bring. Or as Zweig looks back on it: ‘True, we did not regard the handwriting on the wall with sufficient misgiving, but is it not the very essence of youth not to be distrustful, but to believe?’2

Surprisingly, this is only one of the few reflections Zweig made in his book, in which he blamed the intellectual and cosmopolitan elite, of which he was a part. Even more striking is Zweig’s ignorance towards his own privileged, bourgeois position. Zweig’s descriptions and analyses of, for example, the rise of National Socialism or the ethnic conflicts in the Balkans, constantly clash with his own subjective position. Nowhere in his autobiography does Zweig critically address his wealthy Viennese Jewish origins that made it possible for him to have the best education in Austria. His descent was a wildcard that gave him access to a privileged, intellectual, pan-European and cosmopolitan elite. The chapters in The World of Yesterday dealing with the breeding ground of the First and Second World Wars are preceded and alternate with chapters in which we see Zweig traveling through Europe to write and meet up with colleagues in Paris, St. Petersburg, London or the sunny Belgian beaches in Le Cocq.

Zweig’s paradoxical position towards the events his period had to face is illustrative and similar to the current problems of the European project. The dogmatic and Eurocentric attitude of Zweig and his peers corresponds to the ideological crisis Europe is facing today. Zweig revisits the transition from the ‘Golden Age’ (second half of the nineteenth century) to times where ‘light and shadows’ come over Europe (first half of the twentieth century) from a Europhilic perspective. As a writer and intellectual, he (intentionally or unintentionally) refuses to acknowledge that only the privileged cultural elite of which he is a part benefits from the utopian pan-European world he cherishes. In The World of Yesterday Zweig mostly reflects on the impact of the mayhem on his world, on his European dream, on his utopian Europe. As for the impact of the events starting in the first half of the twentieth century on the general population, he considers them from a distance, in a rather cold and intellectual manner. Ironically, as noted in the first paragraph, it was Zweig himself who stressed the importance of a critical distance from one’s own time in order to recognize the law of history that denies us recognition of the beginnings of great movements that come to characterize certain periods.

When we look today at the condition of Europe and the European project, we see that a similar critical distance is lacking. Whereas Zweig took up his pen in an attempt to create this distance, I will use Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo as a vehicle to create a distance to reflect on Europe’s current identity crisis. Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo (Esperanto for ‘The House of European History in Exile’) is a performative installation that pretends to be a museum that looks back from the future (2025) to the genealogy, history and implosion of the European Union (EU), as predicted in Bellinck’s museum. Initiated in Brussels in 2013, presented in Rotterdam (2014), Vienna (2014), Wiesbaden (2016) and Athens (2016), the fictional museum was rebuilt, updated and presented in Mucem (Marseille) during the summer of 2018 at the Festival de Marseille.

The dream of a united Europe rose from the ashes of the Second World War. A collective trauma became the foundation for the European Union. But the further away we have come from the horror of the past, and the bigger the economic prosperity that has resulted from a united Europe, the tinier has become the critical distance from the goals, ambitions, dreams, pitfalls and traps of the European project. Zweig’s story indicates what the consequences can be when one stubbornly perseveres in the dogmatic ideas of a cultural, intellectual and economic elite. More than ever, we must painfully acknowledge that the values upon which the European Union was founded are under fire because Europe’s actions and decisions are in conflict with these fundamental values. Since 2000, Europe has faced one crisis after the other: the financial crisis in 2008, the conflict in the Ukraine with Russia, the bankruptcy of Greece, massive migrations from North Africa, terrorist threats, the rise of populist politicians in various member states, and Brexit. As a result, Europe is more divided than ever. These social, political and economic crises have also generated an existential and ideological crisis. In response to this crisis, we have only repeated and insisted on the old vision of a united Europe. A vision that is similar to Zweig’s: a cultural and intellectual united Europe that in reality is only auspicious for an intellectual elite.

Bellinck’s ingenious fictional museum Domo understands this evolution. By exploring Domo, I would like to addresses the museumification/musealization3 and monumentalization of the European project. By choosing the form of a museum, Bellinck is able to play with museum conventions, and to demonstrate the power of such institutions to impose certain imagery. By manipulating museum conventions, Bellinck has built a mental framework to explore the power structures that want to control the European project and its representation. What will or will not be exhibited equals what will or will not be remembered. What and why will certain elements of the European history be remembered? And what will be the impact and significance of this muzealization and monumentalization of history on the future of Europe? These are the questions that a visit at Domo evokes, and in this paper I shall support this experience with the ideas of Andreas Huyssen, François Hartog and Svetlana Boym.

Dried out sansevierias, Esperanto and EU memorabilia

‘Number 34!’ – this is the extent of the conversation when you receive your entrance ticket at the dingy and dusty reception office of Domo (apart from the clerk’s growling reprimands if you move your chair while waiting before entering the museum). As you first scan this anteroom, everything seems familiar, but strange. Pictures of the presidents of the European Commission are displayed on the wall: Jean-Claude Juncker (2014–2019), Michel Barnier (2019–2022) and Jarosław Kaczyński (2022–2024). Next to the portraits hangs a huge map of Europe’s member states. Taking a closer look, you count 28 member states. Montenegro, Scotland and Serbia have joined the Union. The Netherlands, France and the United Kingdom have left the Union. The sign saying ‘Scotland Office of the EU parliament’ indicates that what we see is not about the European Union as we know it today. All the information panels are in Esperanto, which contributes to the anachronistic structure of Domo. The whole room emits a post-apocalyptic atmosphere. The bored and uninterested office clerk ordering you to enter the museum emphasizes this uncanny feeling. The time you have spent alone in the waiting room does not announce a nice image of what will follow.

Image from Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo in Marseille (2018). Author: Thomas Bellinck/ROBIN. Photographer: Stef Stessel

After the approval of the office clerk to enter the museum, you step into a space that does not correspond to the ‘normal’ image of a historical museum. You enter through a storage room, packed with old promo-flyers for Europe, Lenin-replicas, and bubble-wrap-shrouded busts. Then you arrive at the museum’s entrance, covered in plastic (cfr. pictures). You get the impression that the museum is apparently still under construction. Or is the museum in decay? Or just in renovation? It is an impression that will linger during the whole visit to Domo. Electric cables are sticking out of the walls, furniture is wrapped in plastic, and the limp leaves of the potted plants indicate they haven’t seen a drop of water in months. And as you walk through the exhibition spaces, you are not inclined to think that improvements and progress will be made any time soon. This ambiguous position of Bellinck’s fictional museum is almost a metonymy for the critical situation of the European Union today. Will the European Union persevere in its utopian belief in a Europe ‘united in diversity’ (as one of the exhibition spaces of Domo is entitled), ignoring critical voices, while glorifying and monumentalizing the European project? Or is the Union, despite consecutive crises, capable of putting itself ‘under reconstruction’, in order to update and reinvent it for the future?

Based on the ‘under construction’-atmosphere, and how and what is exhibited, you have the feeling that nobody really cares. Because while strolling around the exhibition space, you don’t have the feeling you have entered a prestigious museum that proudly presents the history of Europe. Bellinck modelled the spaces in Domo on third-rate museums of former Eastern European countries, where, in the absence of a proper budget, the collections consist of memorabilia helping to tell the story and history of a nation. This semi-dystopian feeling is emphasized by the fact that you visit Domo alone. This adds to the impression that what you see belongs to the past. These elements all contribute to Bellinck’s spatial dramaturgy—the visitor goes through the historic phases of the European Union, from its creation to its success; from its recession to its implosion.

The first half of Domo takes you through the history of a united Europe as we already know it. From its creation after the Second World War, as an initiative that encouraged and tightened economic collaboration, to the fall of the Berlin wall. From that tipping point on, Europe and the liberal democracy that it promotes are eulogized in the exposition by celebrating the end of history, and articulating the art of the compromise, which underlies Europe’s triumph. The creation of centralized European institutions, such as the European Parliament, the European Commission or the Central Bank of Europe are proudly presented as stable and loyal pillars of the European Union. But Bellinck also includes the other side of the success story: the cumbersome bureaucratic system imposing regulations and directives, the control of corporate lobbyists, and the callous economic competition between member states that has brought a neoliberal hegemony. What was initiated to look after the interests of every citizen on the European continent has now become a corporate alliance, with economic growth its sole objective, with side effects of growing inequality, austerity and ecological pollution.

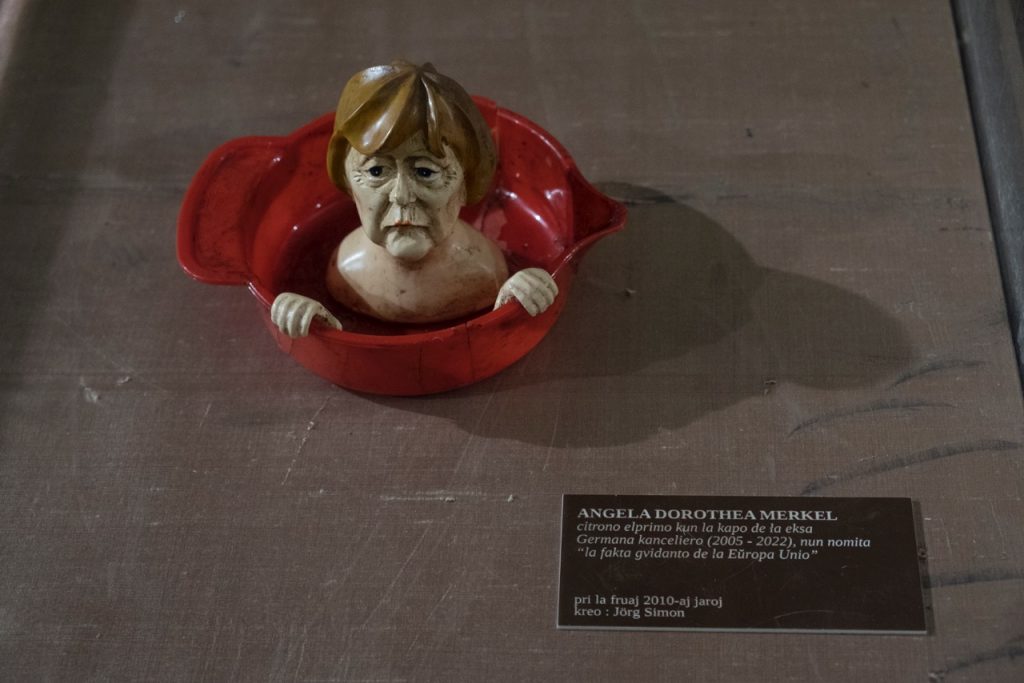

Bellinck displays these aspects of the European Union by covering an entire space with framed business cards of lobbyists, and regulation bills dictating the European standards for the curvature of a banana, the speed frequency of a windshield wiper, and the standard size of a tomato. Another space proudly presents the piles of dossiers that European officers in Brussels have to process. By putting dossiers, business cards or an Angela Merkel-shaped lemon juicer behind glass, Bellinck achieves a sense of anachronism. Generally, when objects are displayed behind glass, we assume that they are artworks or objects that belong to the past. But half of what is displayed in Domo is not part of the past, but of the present. The result is a clash between our concepts of the past’s linear time and the ever-present present. The theatrical setting of Domo introduces what Rebecca Schneider – referring to Gertrude Stein – calls a ‘syncopated time’, a theatrical time where ‘then and now punctuate each other’.4 It challenges a linear conception of historical time and marks that our ‘maniacally charged present is punctuated by, syncopated with and charged by other moments and other times’.5 It is within this moment that a critical distance towards our own time is created. ‘An ethical imperative’ invites the visitor of Domo to reflect on his/her own position within this context.6 What do I know about Europe? What was made possible by Europe? Who benefited from the European Project? And who didn’t? And what political decisions, feuds or different ideological perspectives have brought us to where we are today? Bellinck articulates our historical amnesia, because people start to doubt what is real and what is fictional in the museum. And because it is never clear at what point in time you are visiting Domo, Bellinck’s museum historicizes the present. It is up to the visitor to position and reposition him- or her-self within this present. He is confronted by what Schneider poetically describes as a ‘sticky’ past, and is invited to enter into ‘cross- or multi-temporal engagement’ with what Bellinck presents in Domo as the rise and fall of the European Union.7

Muzealization in a presentist age

The museum as artistic framework enables Bellinck to address these questions. By presenting Domo as if it were a real museum of the history of the European Union, by imitating a set of roles, activities, procedures, discourses, attributes and spaces that we spontaneously connect to a museum, Bellinck manipulates and challenges its conventions and discourse. And because this what-if strategy does not have to fully bear the test of reality, his project has a significantly higher margin for criticism.8 Explicit and alienating at the same time, Domo reveals the apparatus of the museum, determining what will be remembered and what will disappear into oblivion. Bellinck’s main sources of inspiration for developing Domo were the Parlamentarium – the European Parliament’s visitors’ centre, dealing with the role, functioning and the activities of the EU Parliament – and the House of European History in Brussels. The latter was initiated to provide a wide historical context for the decade-long process of the EU, also presenting the contrasting experiences of different European countries and peoples. The House’s aim is to present the development of European integration in a comprehensible way for a broad public, in order to enable future generations to understand the way today’s Union developed. It must become a place that offers the opportunity to reflect on this historical process of unification and on what it means for the present. The House of European History is not an isolated case. Over the last three decades, we have witnessed an increase of similar initiatives in Europe, mainly for economic reasons (especially tourism), but more frequently for political reasons. Nowadays, it is not unusual that – apart from national museums – cities, regions and specific populations have their own museums, telling their history. This renewed attention indicates that history has become a key cultural and political concern in Europe, as the following analyses by Andreas Huyssen, François Hartog and Svetlana Boym will prove.

In Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, Andreas Huyssen observes that it is not history, but memory that we are obsessed with. Memory marks the relation of an individual, community or nation to its past. Traditionally, a museum had the task of providing stable and traditional forms of cultural identity to maintain a connection between the past and the present. But through modern media (photography, video and the Internet), the once stable and strong boundary between past and present has disappeared, according to Huyssen. More than ever, the past has become part of the present in ways unimaginable in the past, challenging how our histories were and are written, mobilized, musealized and monumentalized. As a reaction to this fraught relation to the past, the growing importance of history is complemented by the growing prominence of heritage and the erection of all sorts of museums. Brussels’ House of European History is an example of this trend. Huyssen labels this tendency the hypertrophy of memory, which is in reality a mere re-presentation and commodification of our past. Today this commodification of memory is no longer bound to the institution of the museum, but has infiltrated all areas of everyday life. This is a shift that Huyssen describes as musealization. Huyssen claims that this strong presence of memory and muzealization provides ‘a bulwark against obsolescence and disappearance, in order to counter the deep anxiety about the speed of change and the ever-shrinking horizons of time and space’.9 And although many conservative and populist politicians believe that this cultural muzealization helps us to resists the ravages of hypermodernity, Huyssen warns them that ‘musealization itself is sucked into the vortex of an ever-accelerating circulation of images, spectacles, events and is thus always in danger of losing its ability to guarantee cultural stability over time’.10

Corresponding to Huyssen’s analysis, François Hartog understands our contemporary fascination with memory and its alter ego, heritage, as the expression of a crisis of time. Our experience of time is today saturated by the present, ‘a permanent, elusive and almost immobile present, which nevertheless attempts to create its own historical time’.11 This experience of time, obsessed by the now, possessed by the present, is what Hartog describes as presentism. He sees the proliferation and universalization of heritage as the expression of this presentist age. Because of its expansion, Hartog warns, the invasive and omnipresence of the present is at the same time an obstruction to other perspectives and alternative futures. Consequently, we see today that confidence in progress has been replaced by a desire to preserve and save.

Hence the world appears to us already as a set of museum pieces. Torn between amnesia and the desire to leave nothing out, we try to foresee today the museum of tomorrow and to assemble today’s archives as though it were already yesterday. […] It is heritage that defines what we are today. The movement whereby everything must be transformed into heritage, a movement itself caught up in the spell cast by the aura of the duty to remember, remains a distinctive feature of our present and recent experience.12

As Hartog notes, the current resurgence in remembrance, commemoration and heritage is as much ‘a response to presentism as a symptom of it’ and is intertwined with our contemporary crisis of time and our inability to imagine alternative futures.13 Huyssen shares Hartog’s view and agrees that ‘the faster we are pushed into a global future that does not inspire confidence, the stronger we feel the desire to slow down, the more we turn to memory for comfort’.14 To counteract our continuously rapid-changing society, driven by globalization, the turn towards memory is a way to anchor ourselves, a refuge from a world where time is fractured and instable. Simply put by Huyssen: ‘the past is selling better than the future’.15

What Huyssen describes as musealization and Hartog as presentism, surfaces also in the tensions and struggles of the European project. Despite all the crises Europe has been through, and the future challenges we collectively have to face, Europe’s leaders have been unable to communicate the significance and urgency of a united and decisive European Union. Instead, we have witnessed a retreat into nationalism, where the history and heritage of a nation offers a stable identity on a continent that is getting more diverse, and where the majorities of yesterday are becoming minorities. The House of European History in Brussels is a Zweigian response to these feelings.

With Domo, Bellinck didn’t want to deliver an alternative future. ‘The future is really a pair of glasses through which we try to scrutinize the present’, claims the Belgian theatre maker, and therefore Domo’s concern is the present, not the future.16 Parallel to the insights of Huyssen and Hartog, Bellinck has said that since the second half of the twentieth century, Europe has shifted from a continent where history took place towards a continent that looks back on history.17 The mechanisms of recalling, remembering and commemoration embedded in Domo, derived from our contemporary hypertrophy of memory in our presentist age, are exemplary of Bellinck’s artistic practice.

Entrance from Thomas Bellinck’s museum Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo in Marseille (2018). Author: Thomas Bellinck/ROBIN. Photographer: Stef Stessel

Bellinck’s work focuses on how our recent history has been written, and who was holding the pen. In his work, the lines between fact and fiction are blurred, and thus Bellinck problematizes the way reality is represented by mainstream media, the political recuperation of historical events, and the politics of historiography. In this process of manipulation, fiction becomes a tool to reconfigure historical facts, with the result that the dichotomy between fact and fiction becomes irrelevant. Traditional documentary-theatre re-enacts certain historical events in order to reconstruct what has happened. Bellinck is not interested in the reconstruction of history, but more in the process of writing, editing and assembling history. Bellinck’s documentary-oriented artistic practice encounters the tilting moments of the 21st century, but not in the way we expect in conventional documentary theatre. We can inscribe Bellinck and his projects in a trend of new documentary theatre in Europe that ‘explores the phenomena of the present through an elaborate understanding of media culture, the theory of deconstruction, and forms of theatre that are not primarily based on text’.18 Within this tendency, ‘more complex and hybrid forms of representation’ emerge and pose problems about ‘the status of the image’, ‘the relation with the world beyond the imagination of artists’ and ‘continuously provoke debates concerning the production, representation and status of knowledge, truth and reality’.19 Contemporary theatre makers with a documentary approach such as Christoph Schlingensief, Rabih Mroué, Rimini Protokoll, Dries Verhoeven, Milo Rau and Zentrum für Politische Schönheit, among others, have the ambition to intervene in the world in order to re-engage and reinvent the way reality is represented. With his projects, Bellinck does not have the ambition to unmask or reveal a reality that is truer or more objective than the reality presented by the media or politicians. Instead, he embraces ‘the instability of representation, even its decidedly fictional status, to the point where it becomes common, even fashionable, to announce subjective biases, or to argue for the impossibility of documentary representation tout court’.20 Herein Bellinck and his peers differ from ‘the essentially positivistic pursuit of documentary theatre-makers from the modern canon, such as Erwin Piscator or Peter Weiss. Influenced by Marxism, these makers used their documentary theatre to disclose a reality that was allegedly hidden behind an ideological veil which served the powerful and their worldview’.21

Domo brings up a tension between the fictional and the documented/the real and allows for what Bellinck describes as a ‘discourse analysis’ in the museum. By decontextualizing, re-editing and re-enacting objects, speeches and interviews in a theatrical setting, one shifts from ‘“who-said-things” to “what-is-said” and “how-things-are-said”’.22 This decontextualization and depersonalization creates a critical distance towards our own position and how we relate to our recent past. Because the first half of Domo gives an overview of events or characters that in reality are a part of the past, the museum is experienced as correct and real. The moment you enter the spaces where there are clear references to events of today, this strategy of decontextualization creates this critical distance from our own present. But at the same time, the use of this representational mode of our present suggests that the arrival and exploitation of migrants and refugees, the Demographic Bulimia as described in Domo, belongs to the past. Accompanied by the information boards, mentioning fictional historical terms such as the Second Interbellum, Great Regression, Second Machine Age or May 9th 2025: the Storming of the Berlaymont, Bellinck provokes a temporal disorientation that forces visitors to reflect on what has happened and what has not happened. But Domo never explicitly mentions the price we have had to pay in order to overcome these challenges. Terms such as crisis suicides, crisis widows, radical insecurity do not sketch an attractive and positive view of the future of Europe.

Kristof van Baarle and Charlotte De Somviele have observed that using the apparatus of the museum as an artistic strategy is on the rise in the performing arts field.23 In their analysis and in contrast to what Huyssen and Hartog have claimed, this musealization is part of a larger social and cultural phenomenon and goes beyond the context of the museum. Van Baarle and De Somviele state that in our current ‘experience economy’ – dominated by Facebook and Instagram – the world appears and is shaped as a museum.24 What used to be ours is now separated from us, transformed, and presented as a commodity. This so-called musealization of the self leads to the expropriation of what used to be a part of us, and turns it into a product. When artists like Brett Bailey, Dries Verhoeven, Zentrüm für Politische Schönheit or Thomas Bellinck adopt these mechanisms and employ them with the help of theatrical or performative means, the experience that they trigger goes beyond the experience of loss. Van Baarle and de Somviele argue that this awareness of losing crucial parts of our identity and existence due to musealization is an important experience itself. It is an experience which, according to van Baarle and De Somviele, addresses what it means to be human in a complex society. By placing elements behind a display window in a theatrical and artistic context, horizontal and linear time clashes with the motionless time of the museum, and results in what van Baarle and De Somviele describe as a ‘stand-still’ of images. As in Domo, this allows an understanding of what is displayed as a series of sculptures, which one can mentally ponder. Similar to experiencing Domo, van Baarle and De Somviele claim that apart from estrangement and absurdity, these kinds of musealizations can test and challenge their own impact. Or as the authors summarise, ‘the theatrical musealization appropriates the seeming irreversibility of exhibition in order to re-present it as a proposition.’25 The confrontation with what is exhibited in Domo is Bellinck’s perpetual act of proposing that we think about the ways history is written, archived, remembered and commemorated.

An Angela Merkel-shaped lemon juicer, exhibited in Thomas Bellinck’s museum Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo in Marseille (2018). Author: Thomas Bellinck/ROBIN. Photographer: Stef Stessel

Reflective nostalgia and Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo

As addressed earlier by the insights of Huyssen and Hartog, today’s hypertrophy of memory is the symptom and product of a temporal crisis, a crisis of time. The triumphalism of the age of high modernity with its trust in progress and development, with its celebration of the new as utopian, as radically and irreducibly other, was followed by a fundamental crisis of temporality.26 And like Huyssen and Hartog, Svetlana Boym ascribes the emotional reflexes towards the past to the rise and triumph of modernity and the capitalist obsession with progress. Nostalgia, as Boym explored in her book The Future of Nostalgia, is a resistance to the new configuration of time and space installed by modernity, and resists the modern idea of time – the time of history and progress. In times of acceleration and historical cataclysms, nostalgia inevitably reappears as defence mechanism; the nostalgic cherishes the desire ‘to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology’.27 In the face of memory’s saturation by entertainment, mass media and popular culture, nostalgia tantalizes us: ‘it is about the repetition of the unrepeatable, the materialization of the immaterial’.28 The ambivalence that results from constant recalling of the past confronts us with the following question: ‘are we dealing with a past which has been forgotten or which is too insistently recalled?’29 Or as Huyssen puts it: ‘Is it the fear of forgetting that triggers the desire to remember, or is it perhaps the other way around?’30 Here is Boym’s take on nostalgia: ‘One is nostalgic not for the past the way it was, but for the past the way it could have been. It is this past perfect that one strives to realize in the future. […] Contemporary nostalgia is not so much about the past as about the vanishing present’.31

Boym’s statement describes in a way the atmosphere and the sensation one feels on visiting Domo. The fictional historical distances created by the decontextualization of what is shown in Domo not only triggers estrangement, but also sentiments of displacement and loss about something that has not actually disappeared. These are sensations that Bellinck wants to grasp and insert as a theatrical strategy. Nostalgia functions in Domo as an instrument, but at the same time as a critique of how contemporary museums – such as The House of European History, the Parlamentarium and many others – employ these nostalgic sentiments in order to glorify the past. Reflecting on the present from the future stimulates a very unusual and destabilizing movement of commemoration and remembrance. Departing from that destabilizing moment, Bellinck hopes the visitor reflects on the direction Europe is possibly heading.32 He writes:

I really wanted to trigger in the audience this kind of sensation of going to a funeral of an acquaintance that is actually not dead. The museum had to evoke a sense of nostalgia for something that is still there, as an attempt to talk about death in order to avoid it. […] I think today, I would really say that my museum is an attempt to finally put some things to the grave, to have a proper burial, say goodbye and observe a decent period of grieving. That’s what you need, in order to move and go to the next level, so the new can be born at last.33

In Domo, Bellinck’s nostalgia is not defeatist, nor does it bear malice. On the contrary, Bellinck tries to divest nostalgia of its negative connotations, to transform it into a productive emotion. In her work on nostalgia, Boym, makes a similar move. ‘Nostalgia is not always about the past’, she notes, ‘it can be retrospective but also prospective. Fantasies of the past determined by needs of the present have a direct impact on realities of the future. Consideration of the future makes us take responsibility for our nostalgic tales’.34 Paolo Magagnoli agrees with Boym, and articulates this critical dimension of nostalgia:

Nostalgia is not always the expression of a conservative politics, but may in fact be seen to respond to a diversity of desires and political needs: in other words, along with a conservative, reactionary nostalgia, there can be a critical and progressive one, which can be a resource and strategy central to struggles of all subaltern cultural and social groups. The past can provide positive models of resistance to the status quo and show possibilities which are still valid in the present. In other words, as a longing for another place, nostalgia contains a utopian impulse; that is to say, it reveals a desire for an alternative, better world.35

In fact, Boym distinguishes restorative nostalgia from reflective nostalgia. Restorative nostalgia concerns what generally is considered or defined as nostalgia: it attempts a transhistorical reconstruction of lost homes; it is at the core of recent national and religious revivals; it knows two main narratives – the return to origins and the conspiracy; and it does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition, protecting universal values, family, nature and homeland. Taking time out of time and grasping the fleeing present directs the rhetoric of reflective nostalgia.36 This restorative exercise of nostalgia is what characterizes Huyssen’s hypertrophy of memory, Hartog’s presentism, and is definitely a tendency Bellinck combatted by creating Domo. It is epitomized by the House of European History and the restorative nostalgic politics that it embodies and imposes. In the absence of an inspiring and attractive narrative for the future of Europe and the European Union, after the past and current crises, one has to lean strongly on dreams, beliefs and the achievements of the past. But as Huyssen cautions, ‘the past cannot give us what the future has failed to deliver’.37

Juxtaposed to restorative nostalgia, Boym proposes reflective nostalgia, as an attempt to dwell on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging that arose from modernity. Reflective nostalgia is not interested in the construction of a mythical Heimat (homeland) that is lost; its interest lies in the exploration of different ways of inhabiting many places at once and imagining different time zones. It concerns correlating historical and individual time with the irrevocability of the past and human finitude. By treasuring the fragmentary of memory, reflective nostalgia is oriented towards individual narratives, encountering symbols, narratives and plots from the past in a flexible, critical way.38 It focuses on the mediation of history and the passage of time, on an alternative understanding of temporality, and the superimposition and coexistence of heterogeneous times—all of this in contrast to teleology, or the recovering of what is perceived as Truth.39 A visit to Domo is a constant confrontation between historical time and individual time, sparked by encountering historical objects, facts and symbols, whether real or fictional. Bellinck halts in front of historical junctions and explores who decided what, and for what reasons. It is an invitation to the visitor to reflect on Europe’s motives for certain historical decisions. But Boym’s reflective nostalgia allows us to explore ‘the side shadows and black alleys’ of history.40 It allows us to take a detour, away from the teleological and deterministic narrative of history.

Illustrative for this approach is the figure of Otto von Habsburg, placed centrally by Bellinck in one of the exhibition spaces. Von Habsburg, also known as ‘Otto von Europe’, was the last heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and as an exiled crown prince he grew into one of the most important pioneers of European Unification. He fought Nazism with as much fervour as Communism, became chairman of the Pan-European Movement, and later was a member of the EU Parliament. In 1979, when Otto was in the parliament, he left his seat symbolically empty as a protest, and in order to represent the oppressed people behind the Iron Curtain. In reaction to the borders between East and West, Otto organized the so-called Pan-European Picnics, seemingly harmless, but a key moment in the opening of the borders and the beginning of the end of the Cold War. But as inspiring as the story of ‘Otto von Europe’ sounds, few people have heard of him (including myself). This reconsideration of the figure of Otto von Habsburg might seem a detail in the exposition, but is actually illustrative for what Boym describes as reflective nostalgia. Within the same kitsch-aesthetic as the other objects displayed, Bellinck embeds Otto’s story in Domo not to canonize von Habsburg or to point out our inadequate knowledge of European History. What Bellinck demonstrates by including ‘Otto von Europe’ is the importance of inspiring individuals with a vision of the future – individuals who may be ‘discovered’ by revisiting and reconsidering historic details that seemingly have been forgotten. Although Otto is not in every history schoolbook, he contributed to a united Europe, within the range of possibilities available to him. Europe could not have achieved what it has over the years without the passion of people like von Habsburg. In recent years, the debate about the future of Europe has not been dominated by Otto von Habsburg-like politicians, but by Nigel Farrage, Boris Johnson, Victor Orban, Matteo Salvini, Jarosław Kaczyński or Sebastian Kurz. What Europe needs are new narratives for the future, not the glorified narratives of half a century ago.

With Domo, Bellinck does not impose his new narrative for the future. On the contrary, in the last exhibition space – entitled The Time of Loss – Bellinck sketches the implosion of the European Union in 2025, after the fictional Storming of the Berlaymont on May 9th 2025. After Frexit and Nexit, the remaining members try to keep the Union together, but must compete against the systematic dismantling of European institutions. The end of the Union results in an explosion of unemployment, mass migration of EU citizens to former European colonies, an increase in drug use (with a resulting rise in HIV), and rising suicide rates. As a result of the latter, Vedove Della Crisi (Widows of the Crisis), a movement of wives and mothers of those who saw death as their last solution, is born in Italy. In the rear of the room there is a small door heading to a dungeon. In this dark space there are no information panels or display cases; only a letter on the cold concrete floor, illuminated by light coming from a small window. It is a letter by Bellinck addressed to his friend Lucas, who recently committed suicide, while preparations for the new version of Domo were underway in Marseille. Bellinck writes about building a monument in the last room of the museum – the room the visitor is standing in while reading the letter – to commemorate those who will never get one. A monument to honour the victims of the European policy of the last decade: people in Spain evicted from their houses, a man who shot himself in front of the parliament, desperate farmers who went bankrupt because of Europe’s regulations, a lost generation of young people who could study but could not find suitable jobs, and more. Reading between the lines, we understand that Bellinck’s friend was a victim of Europe’s chosen path.

The dystopian end of Domo could be read as sentimental, or as cynicism on the part of the artist. The pessimistic atmosphere of the last part of Domo presupposes that death or war is awaiting us in the future. Bellinck tries to counter this mood with what follows when you exit the fictive museum: you exit into a sun-drenched bar, overlooking the old harbour of Marseille. Since you entered the museum alone, you also enter the bar alone. This lonely position becomes an open invitation to reflect with the bartender (often Bellinck himself) and other visitors on what they have experienced. By facilitating the possibility for encounters and discussions, and by creating an atypical visit to an unconventional museum, Bellinck’s Domo brings theatricality and performativity into play. As Rebecca Schneider notes, theatricality is inseparably connected to the archive (or museum), and employs it dramatic dimension to preserve the past as the past.41 Bellinck tackles this dramatic element of the archive by inverting its dramatic (and often spectacular) mode. Domo lacks such a theatrical dimension, and is in a way very un-spectacular: you aren’t confronted with moving images or video screens. Instead you have to read a lot. This absence of stimuli demands a different focus from the spectator – one that is more concerned with what is posited on the information panels, and how the exhibition relates to the real present. Thus Domo employs the mode we use to access architecture, an environment, or a museum. As Schneider observes, one performs a mode of access to the museum.42 By making such an artistic choice, Bellinck focuses on the conventions of the museum, on how history is produced and presented, in order to open up the possibility of changing these conventions through the interplay and contrast of fact and fiction.

An off-modern cure for an off-track Europe

What the end of Domo articulates is the irreversibility of history. Regardless of Fukuyama’s thesis on the end of history, or the capitalist obsession with progress, the past – with its various faces – keeps haunting us. History is not a static given that can easily be represented in a narrative, as the House of European History or similar museums attempt to do. The past is fickle, stubborn, and not easy to subjugate. The past does not allow itself to be reduced to an image imposed by political, ideological and economic agendas. Nor does the past allow itself to be reduced to a nostalgic narrative, serving restorative nostalgic feelings. Emerging out of the temporal clash between past, present and future, the concept of off-modern is proposed by Boym as an alternative understanding and inhabiting of time – a proposition to overcome what Hartog has described as the crisis of time.

Compared to fast-changing prefixes such as ‘post’, ‘anti’, ‘neo’, ‘trans’ or ‘sub’, Boym’s ‘off’ refers to ‘off-beat’ or ‘off-key’. In the notion of off-modern, temporality is not linear or teleological; time is out-of-sync. The prefix confuses the sense of temporal direction and is an antidote to our obsession with newness, imposed by a capitalist logic and restorative nostalgia. Boym emphasizes that off-modern is not post-historical, antimodern or antipostmodern. On the contrary, the notion of off-modern is a plea for revisiting the unfinished project of modernity, but based on a different understanding of temporality; one that embeds the coexistence of heterogeneous times.43 As Boym claims, off-modernism ‘makes us explore side shadows and black alleys, rather than the straight road of progress; it allows us to take a detour from the deterministic narratives of history’.44 Such an understanding of time ‘constantly engages with unexplored contexts, the politics of specific places, and inconvenient histories and histories of what if’.45 The confrontation with ‘the radical breaks in tradition, the gaps of forgetting, losses of common yardsticks and disorientations’ produces ‘off-spring of thought out of those gaps and crossroads’.46

Boym’s concept of off-modernism resonates with Schneider’s idea of syncopated time, a temporal constellation where ‘the reverberations of the overlooked, the missed, the repressed and the seemingly forgotten’47 appear. Because, Schneider continues, ‘by touching time against itself, by bringing time again and again out of joint into theatrical relief presents the real, the actual, the raw and the true as, precisely the zigzagging, diagonal, and crookedly imprecise return of time’.48 At the edges of off-modernism artists intervene, asking us to think about alternative genealogies, and encouraging us to be a ‘nostalgic dissidence’ – employing ‘nostalgia as an act of poetic creation’, as an ‘individual mechanism of survival’, as ‘a countercultural practice’ and as the engine ‘to take responsibility for our nostalgia and not let others ‘prefabricate’ it for us’.49 One could define Bellinck’s Domo as an off-modern museum. Domo’s performative dimension embodies Boym’s off-modernist approach, and enables the visitor to explore how historical facts influence our present, how they often produce their own reality, and how historical facts are transformed by ‘cultural memory machines’.50 Domo becomes an instrument to reflect on how the cultural memory of Europe has been produced by adopting restorative nostalgia. With reflection, we may be able to achieve a reflective nostalgic project.

In exploring Thomas Bellinck’s Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo I have tried to demonstrate that Europe’s approach to its past is not only the symptom and product of its identity crisis, but also a symptom and product of a larger social and cultural phenomenon: the hypertrophy of memory in a presentist age. As the insights of Huyssen, Hartog, Schneider and Boym indicate, the nostalgic impulses, the emotional reflex to embrace the past, and the urge to monumentalize one’s individual, ethnic, social or national history can be attributed to the new configuration of temporality installed by modernity, with its trust in progress and its celebration of the new. Nostalgia, embodied by monuments and memorializations, has won ground in recent decades, but is an illusory bulwark against obsolescence and disappearance in a world that is in a constant flux. As Huyssen shows in his book and as Bellinck mimics in Domo, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Communism were the starting point for glorifying and monumentalizing Europe’s project of liberal democracy, rooted in the Enlightenment. The idealized picture becomes problematic when what is being musealized diverges from reality. In the first two decades of this century, Europe systematically undermined its own project by trampling on its own ideological foundations. Facing one crisis after the other, Europe’s judgments were often contradictory to its initial aims and ambitions. Its inconsistency was not the perfect basis to reinvent and update the European project. The consecutive crises were the perfect occasion to start drawing a new blueprint for Europe. Instead, the creed ‘united in diversity’ has become ‘division because of diversity’. Diversity of opinions and perspectives on how to solve current problems has brought indecisiveness.

Bellinck’s Domo is not a utopian future factory. It does not present an idyllic future Europe – the way it could have been if Event A had not happened, or Person B had acted differently. What Bellinck does is to point at what Zweig and his contemporaries ignored: recognizing and acknowledging the handwriting on the wall. This ignorance ultimately caused Zweig to take his own life on 22 February 1948, dismayed and desperate about his Europe. A project such as the official House of European History is symptomatic of the ignorance of the European apparatus. By putting aside the dissatisfaction of average people and their nostalgic feelings, labelling them as conservative or nationalist, one plays into the hands of politicians like Orban, Johnson, Kurz or Salvini. As I have shown, nostalgia is more than an expression of conservative politics; it is a response to the current historical cataclysm with its enormous diversity of desires, expectations and needs. As addressed through Domo, the reflex towards restorative nostalgia can be transformed into a productive, progressive, constructive and critical form of nostalgia. By taking an off-modern approach, Europe can reflect on what the ruins of the past may offer, in order to break the status quo of presentism and save us from a Zweigian solution.

1. Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday. A Biography (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1964), 198.

2. Zweig, 198.

3. “Museumification” is the English term for “musealization”, a term that Andreas Huyssen derived from German philosopher Herman Lübbe. For consistency’s sake, I shall use “musealization” throughout this paper.

4. Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains. Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 2.

5. Schneider, 92.

6. Kristof van Baarle and Charlotte De Somviele, “Als het glas breekt…Het museum als ervaringsstrategie,” Etcetera 33, no. 142 (September 2015): 49.

7. Schneider, 35-36.

8. Sébastien Hendrickx, “Art Presented as if it Were Something Other Than Art,” in Turn Turle! Reenacting the Institute, eds. Elke Van Campenhout and Lilia Mestre (Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2016), 51–56.

9. Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 23.

10. Huyssen, 24.

11. François Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time, trans. Saskia Brown (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 17–18.

12. Hartog, 185–186.

13. Hartog, 191.

14. Huyssen, 25.

15. Huyssen, 20.

16. Thomas Bellinck and Sébastien Hendrickx, “A future history of the present,” Documenta 34, no. 2 (2016), 105.

17. Jasper Delbecke, “The total irreversibility of history: An interview with Belgian theatre maker Thomas Bellinck about the role and importance of history in his work,” Testimony between History and Memory, no. 125 (October 2017), 56.

18. Thomas Irmer, “A Search for New Realities. Documentary Theatre in Germany,” The Drama Review 50, no. 3 (Fall 2006), 20, https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2006.50.3.16.

19. Frederik Le Roy and Robrecht Vanderbeeke, “The Documentary Real: Thinking Documentary Aesthetics,” Foundations of Science 23, no. 2 (2016), 197, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-016-9513-8.

20. T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image. The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013), 36.

21. Frederik Le Roy, “The documentary doubles of Milo Rau & the International Institute of Political Murder,” Etcetera 43, no. 146 (September 2016), 21.

22. Bellinck and Hendrickx, 112.

23. Van Baarle and De Somviele, 47–48. The authors do not use the term ‘musealization’ in their text but the Dutch term ‘museumificatie’. Their analysis of the phenomenon and its definition corresponds to Huyssen’s and Lübbe’s use of the term. For the sake of clarity, I have chosen to use the word ‘musealization’ instead of using two terms meaning the same.

24. The argument made by Van Baarle and De Somviele resonates with Giorgio Agamben’s theory on ‘profanation’. Regarding the fact that Agamben’s philosophy served as a theoretical guideline for Van Baarle’s doctoral research, it is not surprising that the claims he made with de Somviele are permeated with Agamben’s philosophy. See Giorgio Agamben, Profanations, trans. Jeff Fort (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 73–92.

25. Van Baarle and De Somviele, 49.

26. Huyssen, 27.

27. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic books, 2001), xv.

28. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, xvii.

29. Hartog, 16.

30. Huyssen, 17.

31. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 351.

32. Delbecke, 55.

33. Bellinck and Hendrickx, 119.

34. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, xvi.

35. Paolo Magagnoli, Documents of Utopia: the Politics of Experimental Documentary (London: Wallflower, 2015), 9.

36. Svetlana Boym, “Nostalgia and its discontents,” The Hedgehog Review 9, no. 2 (2007), 13–14.

37. Huyssen, 27.

38. Boym, “Nostalgia and its discontents,” 15.

39. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 30.

40. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, xvii.

41. Schneider, 109.

42. Schneider, 104.

43. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 30.

44. Boym, “Nostalgia and its discontents,” 9.

45. Svetlana Boym, The Off-Modern (New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 29.

46. Svetlana Boym, Another Freedom: The Alternative History of an Idea (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 8.

47. Schneider, 102.

48. Schneider, 16.

49. Boym, “Nostalgia and its discontents,” 18.

50. Le Roy, 22.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. Profanations. Translated by Jeff Fort. New York: Zone Books, 2007.

Bellinck, Thomas and Sébastien Hendrickx. “A future history of the present.” Documenta 34, no. 2 (2016): 101–19.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic books, 2001.

⸺. “Nostalgia and its discontents.” The Hedgehog Review 9, no. 2 (2007): 7–18.

⸺. Another Freedom: The Alternative History of an Idea. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

⸺. The Off-Modern. New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Delbecke, Jasper. “The total irreversibility of history: An interview with Belgian theatre maker Thomas Bellinck about the role and importance of history in his work.” Testimony between History and Memory, no. 125 (October 2017): 50–59.

Demos, T. J. The Migrant Image. The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013.

Hartog, François. Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time. Translated by Saskia Brown. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

Hendrickx, Sébastien. “Art Presented as if it Were Something other Than Art.” In Turn Turle! Reenacting the Institute, edited by Elke Van Campenhout and Lilia Mestre, 50–58. Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2016.

Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Irmer, Thomas. “A Search for New Realities. Documentary Theatre in Germany.” The Drama Review 50, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2006.50.3.16.

Le Roy, Frederik and Robrecht Vanderbeeke. “The Documentary Real: Thinking Documentary Aesthetics.” Foundations of Science 23, no. 2 (2016): 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-016-9513-8.

Le Roy, Frederik. “The documentary doubles of Milo Rau & the International Institute of Political Murder.” Etcetera 43, no. 146 (September 2016): 20–25.

Magagnoli, Paolo. Documents of Utopia: the Politics of Experimental Documentary. London: Wallflower, 2015.

Schneider, Rebecca. Performing Remains. Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

Van Baarle, Kristof, and Charlotte De Somviele. “Als het glas breekt…Het museum als ervaringsstrategie.” Etcetera 33, no. 142 (September 2015): 44–49.

Zweig, Stefan. The World of Yesterday. A Biography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1964.

Author

Jasper Delbecke studied Theatre and Performance Studies at Ghent University and Freie Universität Berlin. In 2014 he graduated as Master in Art Science: Theatre and Performance Studies (Ghent University). He is an affiliated researcher at S:PAM (Studies in Performing Arts & Media) at the Arts & Philosophy Department of Ghent University. His doctoral research – granted the PhD Fellowship of the Flemish Research Foundation – explores how the form and the discourse of the essay appears within the field of contemporary performing arts. He has published in Performance Research, Performance Philosophy, Testimony and Documenta.

Email : jasper.delbecke@ugent.be